The Mind’s Laughter: fMRI from Japan.

Whether you know it or not, your brain acts out the words you hear.

Whether you know it or not, your brain acts out the words you hear.

For example, a study led by Naoyuki Osaka of Kyoto University (Japan) shows that the motor cortex revs up in response to words like “belly laugh.” Belly laughs like “Ha! ha! ha!” involve large, fast muscle movements in our diaphragm, chest and vocal cords. Brain activity for those movements may be part of the meaning of “roaring with laughter” or “cracking up.”

But we don’t have to tense our real muscles. Just pretending — in the cortex — is good enough.

Ten centuries ago the first English epic, Beowulf, used a lot of sound mimicry:

With my grip

I grappled

The gruesome fiend.

Try rolling that grrrr, the way they used to. Grrrhhrrhendel. And then imagine some grizzled graybeard, grunting that verse on a grim and grungy night.

Can you feel your hands grabbing that gruesome monster Grendel? Your brain does.

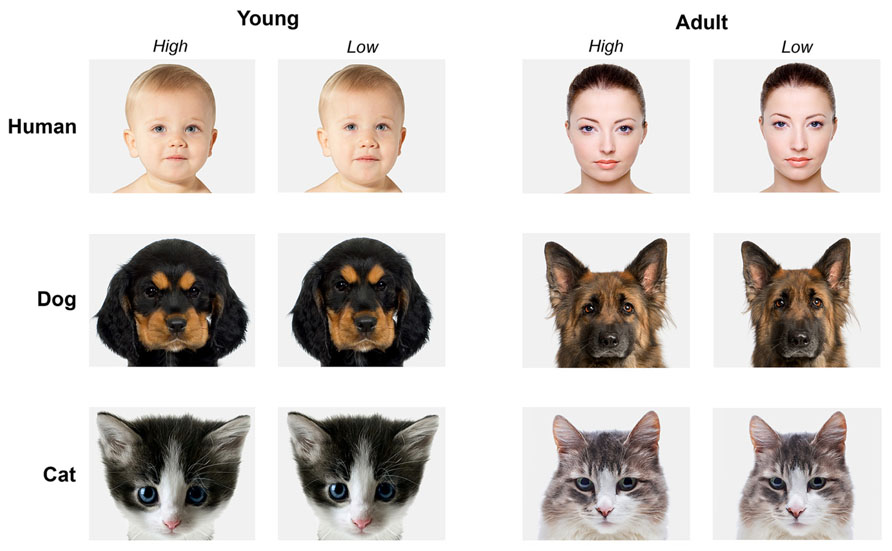

To test whether Japanese words for “big laughs” vs. “polite little laughs” trigger different brain responses, Osaka and his fMRI team chose words that imitate their own meanings.

The Japanese language uses a lot of sound symbolism.

‘Ghera-ghera’ means something like “belly laugh,” while ‘herah- herah’ is more of a polite giggle. When Japanese college students hear “ghera-ghera,” do they mentally imitate a vigorous belly laugh, compared to the polite “herah-hera”? Osaka’s team showed that brain activation in the motor regions of the cortex show a significant difference.

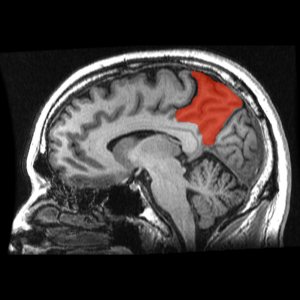

Here are the basic brain pictures. (Figure 1) Notice that they are taken from three perspectives, front, side, and top. If you are not used to looking at brain images, the “side view” (lateral) is looking at a head from the right side, with the eyes looking to the right side of the screen. The view with the “goggles” where the eyes are located is a mirror image of our own face when we look in a mirror. Finally, the bottom image shows the head from the top, looking to the right side of the screen.

Figure 1 Caption: The Japaneses word for “belly laugh” evokes activity in the muscle control regions of the cortex, compared to the Control condition of nonsense words.

Brain experiments always compare two conditions — in this case, the belly laugh compared to nonsense syllables. We can see a lot of brain work going on in the belly laugh condition, and not much in the “control” condition. That “brain work” is the metabolic use of oxygen, which shows up on fMRI — functional Magnetic Resonant Imaging. (The colors are not real, but are added by the computer program to bring out the degree of activity.)

Thinking about belly laughs obviously triggers more brain work than thinking about nonsense words. A lot of that activity is in the motor cortex, the part that controls our outward muscles.

Cortical imitation can happen without any outward muscle movements. In conscious dreams (dreams are conscious) we can fly or struggle with a nightmare monster, but fortunately most of us don’t jump out of windows or fight with our pets in dreams. The outer muscles are mostly inhibited in sleep. Imagined events do not need outward activity.

Words that sound like their own meanings may have been around since early language, around 100,000 years. Some scientists speculate that language may have started from sound imitation. Hunters and gatherers around the world imitate animals. People do it with their pets — and their babies.

Musicians use sound imitation a lot. Words like “Punk Rock” sound choppy, like a drumbeat, while a song title like “Feelings” feels like a flowing melody.

People around the world use sound mimicry. The comic books came up with “Pow!” “Wham!” “Thwack!” and “Zowie!” But “Smash!” sounds different from “Thunk!” or a “Kerplunk!”

Osaka’s group may have discovered brain regions that participate in the Mind’s Laughter, just as Stephen Kosslyn and others found evidence for the Mind’s Eye — our fundamental ability to visualize. (Kosslyn). Others have discovered evidence for something like a Mind’s Ear, a Mind’s Voice, and of course the ever-popular Inner Crooner. (Just sing a favorite song to yourself.) None of those brain events need real muscles or real sensory input. It’s not just laughter that’s echoed in the brain.

Naoyuki Osakaa,*, Mariko Osakab, Hirohito Kondoa, Masanao Morishitaa, Hidenao Fukuyamac, Hiroshi Shibasakic (2003) An emotion-based facial expression word activates laughter module in the human brain: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study, Neuroscience Letters 340 (2003) 127–130.